Pure, Archaic, and Absolute

The

Talent Agent

Iannis Xenakis, House in Amorgos, Greece, 1966. Photograph 2015. View toward cove. Photograph by Leonidas Kalpaxidis.

Secluded in an arid cove, sensuously curvilinear, and hard to find, the François-Bernard Mâche vacation house in Amorgos, Greece, is an architectural hidden gem. Designed by Iannis Xenakis in 1966, this outstanding piece has been obscured in the biography of one of the most idiosyncratic and influential composers of the twentieth century. A founding member of musique concrète, Xenakis also left an exemplary mark on modern architecture. Engineer–cum–prodigal designer in the studio of Le Corbusier, of whom he was both protégé and friend, he was reckless enough to challenge the grand master over authorship, and methodical enough to gain accreditation for his in-house, groundbreaking architectural achievements. Academic literature has scrutinized his contributions: the elegant geometry of ruled surfaces in the Philips Pavilion, the asymmetric rhythm of the undulating glass facade in La Tourette monastery, the mathematical models and pioneering applications of computation in composition, the spatialization of music through light and electro-acoustic clouds in the Polytopes installations. Yet his work as an independent architect, limited though not insignificant, has received little attention.

Hardly published, the vacation house in Amorgos has been living in the shadows of more celebrated projects by its maker—underexposed to architectural criticism, in historiographic limbo, yet intact, like a precious finding from an expedition by an ambitious archivist. 1 Still, among the younger generation of Greek architects and scholars, it has developed a passionate fan base. Sudden appearances increasingly abound—unpublished dissertations, working papers, photographic essays in archizines, scattered Pinterest pins, even a “concrete mix-tape”—but remain far from the attribution it deserves. As this iconic building stoically awaits its place in the history of Mediterranean modernism, it may well be achieving architectural cult status.

Iannis Xenakis, House in Amorgos. Photograph 2015. View from the beach. Famille Xenakis / Xenakis Family Estate. © Collection Famille Xenakis / Xenakis Family Estate.

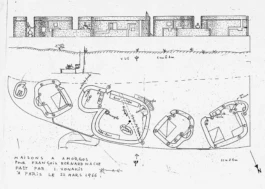

Xenakis first included the house’s plan and elevation in the second edition of his monograph Musique. Architecture, released in 1976.The drawings are presented independent of any reference to the house beyond the subtitle, “Maison de vacances à Amorgos pour François-Bernard Mâche, 1966.” They constitute a graphic manifesto, Xenakis’s proof of concept for the formalization of music as probabilistic (stochastic) composition, setting out the principles of an interdisciplinary science of general morphology. This inaugural, concise publication, which precedes the house’s completion, makes evident its extraordinary properties.

The façade is strikingly uncanny, as if an experimental-music notation system was employed to design the house’s windows. Certainly this is one of his signatures: deep, linear incisions into the wall’s mass, punctuated by small rectangles, and sealed with apparently frame-less glass panels, exposing a masterful, almost brutalist control of concrete. The technique had matured over twelve years in the laboratory of studio Le Corbusier, where it was developed for the stairwell shafts of La Tourette, and later applied in the extension of a sheepfold in Corsica and the unrealized Reynolds House. But here in Amorgos, the pattern is perfectly balanced, flowing joyfully along curved surfaces, unapologetically inviting rays of sun, glimpses of starry skies and open sea.

Then the plan, which is nothing short of a radical metabolism of the Aegean vernacular. Instead of the well-known, indigenous, brilliant-white cubic aggregates, he opts for distinct, free-form curved volumes. The domestic domain is dissected. Detached, the dwelling’s constituents are rhythmically arranged on a platform: a bedroom—a cooking and living room—a guestroom—a bathroom. Each cell is equipped with basic essential furnishings, built-in benches and beds in accordance with the local tradition. In these sparse interiors, a sense of discomfort is detected, implying a sophisticated practice of austerity. The philosophical art of living simply meets the refined scarcity of the Aegean archipelago. It is a perfect fit for the ascetic intellectual’s disposition.

Iannis Xenakis, House in Amorgos. Photograph 2015. View from the beach. Photograph by Leonidas Kalpaxidis.

On the contrary, the house’s outdoor territory, delimited by the platform spanning the two retaining walls, is gratuitous. It is an all-too-willing container of the indolent life of Mediterranean summer—alfresco baking, dining under the vineyard, siestas, sunbaths, late-night gatherings. Exposed to the Etesian winds, refracting the big blue, capturing the sculptural chiaroscuro of the curvy volumes, the outside space is an active figure rather than a background to the domestic interior. Its front faces the sea, in whitewashed concrete. Its back is carved out of the hill, paved with stone. A narrow staircase climbs onto the flat roof of the largest volume, to the affordance of the open sky.

Mâche was a friend rather than a client. It was Xenakis who offered to design the house for him. He was a fellow in the Groupe de recherches musicales at the time. Today, he is the caretaker of Xenakis’s legacy. By all means, the French composer should be recognized as indispensable in the materialization of this plan. Having received his diploma in Greek archaeology, Mâche was familiar with early Aegean civilization and quite possibly visited active excavation sites, like Minoa in Amorgos, as a student. He was a philhellene and a naturalist, an aficionado of Giorgos Seferis and of Greek mythology. He traveled regularly to Athens and the Cyclades archipelago.

Iannis Xenakis, House in Amorgos. Photograph 2015. Photograph by Leonidas Kalpaxidis.

Long before mass tourism celebrated the commodified pleasures of Ios, Santorini, and Mykonos, the Cyclades were rough and reclusive, a destination for uncompromising travelers, determined escapists, poets, and artists. Amorgos is their easternmost island, long, narrow, and mountainous. Imagine this place in the 1950s. No motorways. No electricity. Solitary, whitewashed chapels. Arid landscape domesticated by terraces. Dry-stone retaining walls. Ancient footpaths. Enchanted, the young composer spent his summers there camping, recording sounds of birds, and observing the night sky with his telescope. In 1965, he bought a plot of land in a remote cove in its southern part. 2 It is an inclined terrain halfway between the ridgetop and the seashore, and a two-hour walk from the closest village. The house is saturated with the essence of this place: pure, archaic, and absolute.

Iannis Xenakis, House in Amorgos. Photograph 2000. The front terrace. Detail of the linear incisions on the surface of the facade. Photograph by Sophia Vyzoviti.

It possesses a resilient appeal, emanating from the determination of the two musicians. Bound by a lifelong friendship, their trust and affection developed in the decade that spanned the design and its realization. This house is a token. The designer, exiled to Paris during the Junta because of his active participation in the Greek civil resistance, longs for a heimat. The owner, traveling between the two countries, summons local architects, pursues legal matters, conveys technical advice, and manages its construction. Yes, architecture can come through, despite and against the impossibilities of place and history, with the persistence to fulfill an ideal. In this case, the shared affection for a mythic place provided both subject matter and testing ground for a twentieth-century avant-garde.

Its power lies in its Janus constitution. It is apparently futuristic, with a face turned toward the past; contemporary and abstract, yet evoking premonitions of prehistoric structures, of tribal huts and spouted bowls crafted thousands of years ago. Its bold form recalls the elegance of Cycladic idols. The universality of the International Style becomes deeply embedded in localisms, and cultural context. It even promotes a minimalist lifestyle that renounces luxury, encompassing the Aegean tradition of making do with little recourse. For the younger generation of architects in Greece, coming of age in the midst of interminable austerity measures, it speaks directly to the heart.

The Talent Agent was played by Sophia Vyzoviti in Flat Out 2 (Spring 2017).

1 The François-Bernard Mâche vacation house has been included in two publications: Iannis Xenakis, Musique. Architecture (Tournai, Belgium: Casterman, 1976), and Iannis Xenakis, Music and Architecture: Architectural Projects, Texts, and Realizations, trans. and ed. Sharon Kanach (New York: Pendragon Press, 2008). ↩︎

2 Konstantina Kalfa and Mara Papavasileiou, “Corresponding the Construction of F. B. Mâche’s Holiday House in Amorgos, Designed by Iannis Xenakis” (lecture, French Institute of Athens, Athens, Greece, November 20, 2015). The facts regarding the materialization of the house were drawn from Papavasileiou’s lecture, presented at the conference Paris-Athens: 1945–1975, which details correspondences between Xenakis, Mâche, and the local architects. ↩︎

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts