How to Write an Exhibition Review

The

Opinionator

These are sorry times for the architectural exhibition review. So many offer sanctimonious platitudes instead of criticism. Too few pass judgment. Perhaps this is why an extraordinary number of academics, art directors, curators, mayors, and public relations consultants have leapt to embrace the exhibition format as a promotional tool. Reviewers are unlikely to hold them accountable.

From the promoters, we invariably hear about the format’s importance: biennials, triennales, annual expos, or one-off museum shows draw tourists to cities, produce new kinds of audiences, tell stories about architecture, and on a good day, advance ideas for the discipline. Architectural exhibitions are apparently very good at doing good in multiple domains.

But from the critics we rarely hear whether these exhibitions are any good beyond their attendance numbers. Do they bring us closer to understanding what is significant or insignificant architectural work? Do they solicit surprising ideas? Could they have been staged better? Addressing questions like these through informed, evaluative writing used to be the sine qua non of the exhibition review genre. It needs to be again.

I’ve been comparing the curatorial statements of architectural exhibitions to exhibition reviews a lot lately and find that exhibition culture is imprisoned in a bilateral stalemate. By and large, critics today tend to stand in the same relationship to exhibition content as curators do. Both sides systematically avoid polemic and controversy. Both sides attend comfortable, safe ideas. Neither challenges the other. Architectural exhibitions are victims of this symmetrical malaise.

In North America, the malaise is symptomatic of a broader tendency that the economist Tyler Cowen identifies in his recent book, The Complacent Class. Cowen argues that Americans have traded their trademark restlessness and uncertainty—in education, technology, business, domestic life, and so on—for stability and affirmation. In design criticism, the malaise registers in three kinds of exhibition review today: the Yes Report, the No Review, and the Maybe, So-So. Although each evidence degrees of competency in thinking and writing, allow me to elaborate on the most inadequate versions and their fallouts, for the sake of making an argument about where the exhibition review needs to go next.

The Yes Report

This commonplace, objective summary typically affirms given curatorial narratives, prioritizes descriptive copy, and quotes heavily from press releases. The writer does little more than confirm Oscar Wilde’s observation that “most people are other people [and] their thoughts someone else’s opinions.” The Yes Report is a sales pitch; its protagonist, the yes-man, is the salesperson.

The problem with the Yes Report is that it too readily accepts givens. It seldom elaborates on an exhibition historically, theoretically, or comparatively. It presumes that intellectual authority (that is, ability or expertise) equates with institutional authority (position, influence). It presupposes that taking a position, a point of view, equals having a position, an institutional job. It rarely does.

Credential checking does not move architectural culture forward. The deferential reviews of 2014’s Venice Architecture Biennale, Fundamentals—a polemical exhibition by the architect-critic Rem Koolhaas proposing to replace “architects” with “Architecture”—ensured the exhibition was dead on arrival. Few critics dared to assess the choice to focus on ready-made construction materials. Without polemical criticism, architecture culture carried on as if nothing happened.

In contrast, think back to 1956’s This Is Tomorrow. Like Koolhaas, its curator-architects also embraced the role of critics, and radically proposed replacing artistic unity with eclectic variety against the grain of the modern movement. The exhibition activated a community of disagreement: an outraged establishment, a confused public, and scathing critics. Diverse views exploded architectural culture in groundbreaking ways. Unlike Fundamentals, This Is Tomorrow got the polemical response it deserved. Architecture culture was never the same again.

My point here is that neither intellectual diversity nor cultural advancement is possible when a critic operates as a curator’s flunky. The Yes Report can only ever produce what Marcel Proust called a “fashionable milieu”: a context where everybody’s opinion is made up of everyone else’s, or crowdsourcing as argument. Proust preferred a “literary milieu”: a situation where everyone’s opinions are different. For the sake of architectural culture today, we should too.

The No Review

This infrequent spoiler usually delivers a negative point of view. It has no qualms about taking issue with an exhibition’s content or premise. It tries to situate ideas in a broader landscape of events, both historical and contemporary. As professional critics have abandoned it, it has become the preferred writing genre of architect-practitioners. It is a necessary if not entirely sufficient genre. Yet it is the most vilified review type in our field.

The problem with the No Review isn’t the “no” part. It’s the reception part. These days, skepticism—nay, criticism—brings contempt, ridicule, and disapproval to its author. For reasons that I will never understand, attempts to counter-situate, analyze, and interrogate exhibitions are no longer appreciated. Expressions of adverse opinion are better done in private. A No Review is considered bad manners, like eating with your mouth open.

Consider Patrik Schumacher’s incensed response to 2015’s Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB), The State of the Art of Architecture, and the equally incensed reactions to it. “Absolutely out of line,” an east-coast architectural historian muttered to me at a conference six months later. True, Schumacher ranted about the CAB’s digital lacuna. True, most didn’t agree with his point of view (nor did I). But, for heaven’s sake, at least he had one. And at least he had the gall to go public with it.

And here is the dilemma: just as the Yes Report has been rendered innocuously communal, the No Review is dismissed as awkwardly personal. Our field’s hostility toward the No Review marks an ominous turn in our collective discourse. Colleagues seem to like or dislike criticism of exhibitions to the extent that they like or dislike the critic. This shorthand is ridiculous.

It’s also backward. There can be no advance in architectural culture when unpopular opinions are collectively smothered, a focus on content is subsumed by the personal, and conformity choirs drown out idiosyncratic thinkers. The No Review is one of the best bets we have to construct Proust’s literary culture. But to do so it needs to land in an open, receptive environment, while avoiding the charge of being merely self-promotional. To preclude such an environment is to practice risk aversion.

The Maybe, So-So

This equivocating, nothing-at-all review appears frequently in peer-reviewed journals and the popular press. It generally takes two dithering forms: the hedged (a combination of yes and no opinion) and the point-less (neither yes nor no). It’s conspicuously diligent and utterly useless.

The problem with the Maybe, So-So is that it neutralizes positive and negative criticism in a self-canceling, zero-sum game. It might praise certain aspects of an exhibition but undermines others. It might be snide or nasty in tone, but pleasantly neutral in content. It might be negative throughout, but suddenly conclude on a positive. It might heavily rely on conditionals like “however” and “but.” In any one of these ways, the Maybe, So-So adds up to a big naught, an opinion vacuum.

Michael Sorkin nailed it when he described the flip-flopping strategy of the former New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger as “Jesuitical vacillation, occluded by a thick applique of qualifying rhetoric.” As Sorkin put it, “The reader [is left] with the impression of an opinion but with no recall as to what it might actually be.” This is the most succinct summation of the maybe, so-so effect I can think of.

The Maybe, So-So is the preferred genre of those who want to appease their institutional leaders and academic colleagues, look smart without making enemies, and showcase their political skills by balancing the personal with professional. None of them is motivated by the need for cultural discourse. All of them are driven by the desire for self-preservation.

Exhibition culture is done a great disservice when critics look over their shoulder in anticipatory damage-control mode. Gustav Mahler once said we should be “neither depressed by failure nor seduced by applause.” Quite right. Exhibition culture needs critics who take risks and express opinions without fear of causing personal affront or facing institutional retribution.

OK, enough said. If Yes, No, and Maybe, So-So are inadequate, how then, to write an exhibition review today?

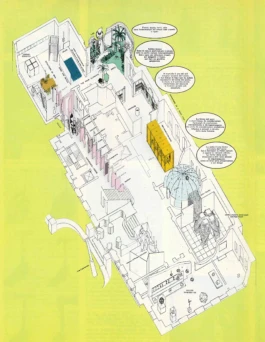

Descriptive criticism in axonometric form. Published in

Ugo La Petra, “MAN transFORMS: universe e pane quotidiano,”

Modo 6 (Jan.–Feb. 1978), 40.

And Now What?

Let me propose instead the And Now What? Revision, the exhibition analysis that asks three simple questions: what is being done, what is not being done, and what should be done? It answers these questions in four moves in the right mix—just like a good cocktail.

First, it revels in the art of explaining. It deploys descriptive criticism—visual and verbal—as opposed to descriptive summary. It succinctly relays an exhibition’s intellectual concept. It vividly describes the physical arrangement of drawings, models, and films, in relation to floors, walls, and ceilings. Take the pithily annotated axonometric drawing of Hans Hollein’s MANtransFORMS from 1976, published in Modo, for instance. This is descriptive criticism at its finest: completely visual.

Second, it interprets. It unpacks the implications of an exhibition’s concept by elaborating and expanding on the given framework. Robert Bruegmann’s 2017 Journal for the Society of Architectural Historians review of Beatriz Colomina’s Playboy Architecture, 1953–1979 at the Elmhurst Art Museum in 2016 is excellent in this regard. Bruegmann reads the Playboy material as saying more about the cultural contradictions of “a long-lost world” than about modern architecture. His sociocultural interpretation is a new dimension for Colomina’s research.

Third, it evaluates. It offers a decisive point of view. It diagnoses successes and failures. It passes value judgments. Florian Idenburg’s concise review for Metropolis of 2015’s Shelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angeles at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum is a good example. With great economy, Idenburg assesses the exhibition brief (“curators have lost the plot”), the collective result (“doesn’t get very far in the rethinking”), and its underlying message (“reinforces market fundamentalism”). No question, we know where he stands, and where the exhibition falls.

Finally—and this is the “and now what” part—it projects. It uses the exhibition to speculate on architecture’s future directions. What might follow? What should follow? And here I turn to one of my favorite exhibition reviews: Reyner Banham’s brilliant take on This Is Tomorrow for Architectural Review. Banham ventures the submissive limits of New Brutalism through the Smithson-Henderson-Polozzi contribution, and its future promise as “concrete image” through Voelcker, Hamilton, and McHale’s. It provides a foundation and opportunity for his theory.

The release provided by the And Now What? is that it requires critics to stand in a different relationship to exhibition content than curators do. It asks them to construct a platform for disagreement by setting out positions to attract (or deter) future professional and public audiences, by being willing to judge an exhibition, by questioning and situating curatorial assumptions, and by proposing alternatives that challenge the status quo. It imposes upon them the obligation to produce discursive asymmetry.

With 2017’s second Chicago Architecture Biennial, Make New History, just around the corner, it’s time for critics, journalists, scholars, opinionators, and scorekeepers to measure the results against intentions, explain and interpret the designs and layouts, weigh idea against idea, design strategy against design strategy, history against the present, and the present against the future. In other words, give the exhibition the review it deserves, for better and worse.

The Opinionator was played by Penelope Dean in Flat Out 2 (Spring 2017).

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts