Die Techie

Scum

The

Muckraker

Douglas Rushkoff’s best-selling 2016 book, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, begins with an act of social protest: “One December morning in 2013, residents of San Francisco’s Mission District laid their bodies in front of a vehicle to prevent its passage. Although acts of public protest are not unusual in California, this one had an unlikely target: the Google buses used to ferry employees from their homes in the city to the company’s campus in Mountain View, thirty miles away.” 1 However unlikely the target may have seemed to Rushkoff, the object of the protest is not hard to understand. In 2012, one year earlier, the median sales price for a house in San Francisco reached a new record of $750,000. (By way of contrast, the median sales price for a house in the United States today is $256,000.) The moving forces behind this market upturn and the ensuing protests are easily traced to the bus’s destination: the tech industries of Silicon Valley, forty-five miles south of the city of San Francisco. These industries’ enormous growth and wealth are putting upward pressure on every facet of the local economy. The 2013 barricading of the Google bus was only the beginning; just over five years later, the median sales price for a house in San Francisco has doubled to $1.5 million, and protests continue to this day. 2

San Francisco in relation to the larger Bay area. Map by James Goggin.

That the market has escalated so far, so fast may have something to do with the unique geographical situation of San Francisco. Limited to seven by seven square miles, this relatively small area serves as the symbolic and actual hub of the Bay Area, a region that covers sixty-nine hundred square miles. While the city is dense, with a population of 864,816, it is dwarfed by the Bay Area’s larger population, 7.15 million. It is hard to imagine a place and time in which an area so small has become the demographic, economic, and political focal point of an area so large.

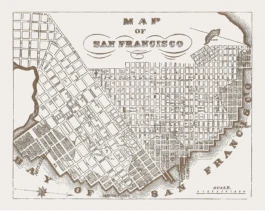

San Francisco’s traditional urban grid prior to 1950.

What makes this forty-nine square miles the focus of intense attention is not only its age and location, but its traditional urban characteristics. San Francisco sits on a grid of mixed-use, anthropometrically scaled blocks held together by publicly shared street space. Like the rest of North America, Bay Area municipalities were produced by an aggregation of the traditional city block up until 1950 and, since then, the onset of large-scale, single-use superblocks, including subdivisions, office and industrial parks, and shopping centers. There is, perhaps, no more beautiful result of traditional, block-level aggregation anywhere else on the continent than in San Francisco. The contrast between its strictly orthogonal layout and its dramatic, complex topography produced blocks and streets that are known all over the world. With such a limited amount of this development, however, San Francisco is a fixed commodity for which there is explosive demand.

Hypothetical extension of San Francisco’s pre-1950s block structure down the peninsula. Map by James Goggin.

The implication of the limits of this commodity can be revealed in a simple thought experiment, whereby we imagine that San Francisco’s pre-1950 grid of blocks and streets had not been preempted by the large-scale, master-planned cul-de-sac development, but had instead been extended, block-by-block, down the peninsula. In this scenario, there would be no housing shortage and no gentrification, and there would be enough “San Francisco” to house the entire Bay Area population. Another way of describing this is that if San Francisco had continued to grow as blocks and streets, it would now consist of five boroughs, each roughly the average size of the five boroughs that make up New York City.

This, then, is the story of two cities. The first is the fictitious five boroughs of San Francisco made up of the region’s highly prized urban blocks, held together by public street space and dominated by bipeds. The second city is what exists—a single borough comprising the present populations of San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley, leaving the rest of the population spread across the remaining Bay Area counties in low-density, discontinuous, master-planned subdivisions and office parks. The difference between the two cities revolves around the urbanism of the missing four boroughs and its deficiencies with regards to the actual borough of San Francisco. These deficiencies take obvious forms in their outward expression—the lack of public space, representational civic architecture, and pedestrian environments—as well as in overall aggregate inflexibility. 3

The central business district (CBD), the Market Street Corridor, the Mission District, and Dolores Heights are multi-use street spaces with a long list of amenities that are the fruits of open-ended urban aggregation. San Francisco’s foreclosure at the limit of forty-nine square miles has capped these virtues. It is this inability to expand that has brought hordes of deep-pocketed entrepreneurs to a fixed housing market, and forced hardships—including massive city-wide evictions—that politics is unable to understand, let alone resolve. Until the urbanism of the missing boroughs is understood, until the deep structure of the problem is revealed, no remedies will succeed.

Foster + Partners, Apple Park, Cupertino, California, 2017. Photograph 2018. Aerial view. Photograph by Daniel L. Lu.

A good place to start in developing this understanding is with the source of the problem: the suburban corporate campus. Among the most conspicuous of these is the new Apple Park campus located in the suburban city of Cupertino, forty-five miles south of the city limits. Designed by the famed English architect Norman Foster, the 2.8-million-square-foot headquarters was completed in 2018. This $5 billion office building was built on 175 acres of artificial rolling hills embellished with nine thousand newly planted trees. It is designed to accommodate twelve thousand Apple employees. The form of the building is a closed cylindrical loop that is one mile in circumference and 1,512 feet in diameter. Its inner courtyard encloses thirty acres. The campus is fenced and bermed against its immediate surroundings within the city limits of Cupertino; its ceremonial vehicular entrance is through a 755-foot-long tunnel.

The entire tech industry was invented in the low-density, low-grade sprawl of the missing boroughs and exported from there around the world. It is because of this unprecedented global reach that these companies have become the largest and most profitable in the world. Well aware of the limits of virtual technologies, these digital companies did what the largest corporations have always done: translated their bank balances into representational form. As a type, the corporate campus emerged from this translation in the second quarter of the twentieth century, only to expand and flourish in the third quarter. 4 By the fourth quarter, however, the large, custom-built corporate headquarters gave way to the generic office park. Deferring to fluctuations in employee populations, corporations abjured their symbolic aspirations in order to accommodate viable exit strategies for lean times. In other words, the custom-built corporate building was recognized for what it had become by the end of the twentieth century—a white elephant.

By 2000, however, a revival of the corporate campus emerged, almost exclusively via the West Coast tech companies. Beginning with the glorified office park strategies of the Microsoft Campus in Redmond, Washington (occupied in 1986), and Apple Campus One in Cupertino (occupied in 1993), these early tech headquarters followed the reigning wisdom of the day—nondescript buildings capable of being leased out at a moment’s notice. This wisdom contained a polemic against conspicuous corporate wealth best represented by the laid-back non-uniform of Steve Jobs’s turtleneck and jeans. As these companies grew in size and influence, they overcame their reticence toward spectacle. Today, they are all involved in the translation of their enormous bank balances into conspicuous symbolic statements.

There have been many architectural critiques of the Apple Campus since its opening, but its place in, and impact on, the larger urban landscape of the Bay Area has received less attention. It is in this larger landscape that the butterfly effect is on full display: Apple builds a workstation in Cupertino, and forty-five miles north a block full of residents are evicted from the Mission District. Unlike the butterfly effect, however, the source of this disruption and the means of its amplification are easy to identify.

The California Environmental Impact Report on the Apple Campus, completed before construction began, concluded that only 10 percent of the working population of the campus would live in Cupertino. Even so, this would nonetheless lead to an immediate increase in demand for Cupertino housing by 284 percent. Also reported was that 1.5 percent of commuter trips to the Apple Campus would be by public transport. 5 From the start, it was known that access to and from the campus would be private. This is typical of all the major Silicon Valley companies. Capitalizing on density, a private transport network was invented to extend corporate reach forty-five miles north into the heart of the forty-nine square miles of San Francisco. The need to compensate for the lack of appropriate amenities in the large, low-density master-planned subdivisions spread across the four counties of the Bay Area made a direct link to the public resources of San Francisco inevitable.

Given that all of the tech companies were doing the same thing, an unprecedented level of gentrification was not difficult to predict. Nonetheless, it seems to have been overlooked by almost everyone directly involved in the planning of their new facilities. The first misstep came in the form of large buses, the most visible signs of a new, private mass-transit system that inverted the commuting patterns of the Bay Area. The economic logic was straightforward. The young demographic of coders was attracted to urban life, and the squeeze put on the surrounding suburbs could be reduced by encouraging a daily sixty-minute commute. Additionally, each transplant from the pedestrian environment of San Francisco yielded one fewer parking space required in Cupertino.

Once the culprits had identified themselves with their large rolling billboards, San Francisco began to add it all up and the shit hit the fan. In their defense, the management at Apple was as myopic as they had been in the planning of the campus. The lead designer, Jony Ive, was quoted as saying, “We didn’t make Apple Park for other people, so a lot of the criticisms are utterly bizarre, because it wasn’t made for you!” 6 Feigning ignorance of the havoc they brought to the real-estate markets as a whole, and especially its symbolic center, Apple dismissed any calls for greater corporate responsibility as “bizarre.”

With this comment, we are left to speculate on the sentiment that led John D. Rockefeller Jr. to conceive the first corporate campus—Rockefeller Center—as a badly needed urban-renewal project for Midtown Manhattan at the height of the Great Depression. One might conclude that, like chivalry, corporate largesse is dead. The progressive pact forged at the turn of the twentieth century between private and public interests has long been overwritten by the Darwinian logic of neoliberalism. Once unselfconsciously altruistic, the tech industry today seems unable to even conceive of a good that exceeds its share value. Rockefeller has nothing on these digital robber barons.

The new Apple Park campus located in the suburban city of Cupertino. Map by James Goggin.

Facebook, Google, and Apple’s private bus line routes between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. Map by James Goggin.

Predictably, these new barons have given rise to a new generation of muckrakers. As the longtime symbol of urban mass transit, the opponents of gentrification found a highly ironic emblem on which to focus their considerable wrath. Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Apple, along with smaller Silicon Valley companies, had discreetly deployed a large private transit system in the form of a fleet of buses. The effect of this system on San Francisco was anything but discreet. It quickly manifested in the buses’ very visible contribution to urban traffic and their brazen use of public bus stops as pick-up and drop-off points. Less visible but more damning, rents close to those bus stops were calculated by resident advocates to be 20 percent higher than those in comparable areas. These stops became the true epicenters of tech-driven gentrification and the site of the 2013 human blockade Rushkoff described in his book.

As eviction rates increased, and protests refused to die down, the corporations’ PR offices went into full swing. The companies’ commitment to bolstering the local economy had little effect on neighborhood sentiment. That commitment was, apparently, not local enough. Appeals to San Francisco’s green consciousness—Google noted that the shuttle program saves more than twenty-nine thousand metric tons of CO2 per year—also fell flat. As real estate prices rose and evictions escalated, broad demographic shifts that would normally take place over decades took place over months. A destructive political polarization took hold.

There is a page on Facebook called “Die Techie Scum.” 7 The page is maintained by “some dude named Zeke,” whose avatar sports a nose ring and a soul patch, and who refers to himself in the third person. The page, which has six hundred followers, consists largely of reposts of articles critical of the tech industry and the gig economy, with provocative titles like “Five Inspiring Tech Entrepreneurs Who Will Be Hanged in the Revolution,” “Twitter Employee Complains About Being ‘Broke’ on a $160,000 Salary,” and “San Francisco tech worker: ‘I don’t want to see homeless riff-raff.’” In true muckraker fashion, Die Techie Scum aims to expose the corrupt captains of industry, like Silicon Valley’s conservative mouthpiece, Peter Thiel, and the feckless Marc Zuckerberg, who, after aiding in the rise of a reality TV star to the highest office in the country, is in a seemingly constant state of wonder as to what the fuss is all about. The page shows photos of well-attended marches, with protesters carrying hand-painted banners protesting evictions and densification. It also shows photographs of widely distributed flyers pasted up in public spaces with slogans like “Brogrammers off the block” and their own “Die Techie Scum.”

The roots of the “Die Techie Scum” movement can be found in the same Vietnam-era politics that took over San Francisco and Berkeley in the sixties, and which has only intensified since. 8 In defense of the broad diversity of San Francisco, pro-resident groups like Eviction Free San Francisco began to rail against the tech industry, framing their globalist adversaries against the “locals” who take to the streets defending their right to the city. Eviction Free San Francisco also has a Facebook page that promotes regular meetings on the first and third Wednesdays of each month at 6 p.m. Risking a gross oversimplification, leftist movements such as Die Techie Scum and Eviction Free San Francisco subscribe to a kind of folk politics of localism, direct action, and a relentless, grassroots anarchism that rejects any overt organizational structures. Following the precedents of the sixties, these politics are defined against the forces of modernity, abstraction, complexity, globalization, and often technology itself. Yet it is precisely these forces that are driving the extraordinary economics of the Bay Area, as well as the citizens of the City of San Francisco, out of their homes. Unable to understand, let alone engage, the forces against which they struggle, their failure is assured.

As the Left remains focused on establishing small and temporary spaces of non-capitalist social relations—such as eviction-free zones—the buses continue to run and real estate values continue to soar. By ignoring the deeper structural problems, the critics ignore the larger forces that are non-local and rooted in the economic and physical infrastructures on which they depend. This dated form of politics has focused on building bunkers to resist the encroachments of global neoliberalism rather than any sort of tactical rapprochement. In so doing, the Left has adopted a strictly defensive position and are thus incapable of articulating an alternative vision of the city. Today, the politics seems to have devolved into in a form of a morose, self-righteous NIMBYism that actively works against its own egalitarian interests.

Small and local will not win the day. Despite the rightness of their cause, the opposition is failing. No one believes that evictions will stop. In the meantime, activists continue to fight densification as some kind of literal corporate “invasion,” confusing the crucial differences between gentrification and urban density. 9 Given the extraordinary economic and demographic pressures resulting from mass population displacement, San Francisco must grow, as all cities need to in order to meet population increases. By resisting significant increases in density, however, Bay Area politics runs the risk of rapidly turning one of the most beautiful cities in the world, with one of the most progressive political agendas, into the exclusive playground of the 1 percent.

It should be made clear that the densification of San Francisco’s seven-mile square is not sufficient to solve the problem. Returning to the thought experiment whereby we imagine that the city’s grid of blocks and streets had not been preempted by large-scale, master planned cul-de-sac development, we can consider the prospects of extending the aggregate block structure of San Francisco down the peninsula. Were aggregate growth to be supported in a manner that was consistent with the technical, financial, and political logic of urban production today, supply could meet demand, and there would be no housing shortage or evictions, and no ten-hour-weekly commutes on private buses. There is, however, no room for nostalgia here. There is no faster way to accelerate gentrification than to adopt a neo-traditionalist’s position under the mistaken impression that we can simply reproduce, in today’s economy, blocks that were laid out and built one hundred years ago.

The problem is not techie scum (are they not workers themselves?), nor is it the dated politics of the Bay Area. The problem would not be solved by moving tech companies into the city (as the sixty-one-story Salesforce Tower has recently done). It would, on the contrary, be made worse. The problem is, of course, the highly desired qualities and characteristics of the four missing boroughs. That neither the techies nor the lefties understand the most basic of urban dynamics is unfortunate, as it produces straw men in the pursuit of false debates. Even more unfortunate, however, is this lack of understanding by the city’s institutions, which seem powerless even to formulate the problem correctly.

The basic urban dynamic is this: after flourishing in the immediate postwar era, the large, custom-built corporate headquarters had been in decline for decades. Deferring instead to fluctuations in employee populations, corporations built generic office space providing viable exit strategies for lean times. In other words, the custom-built corporate building was recognized for what it was. There is no exit strategy for the Apple Campus. The missing boroughs must make way for the qualities and characteristics of actual boroughs and, given the magnitude of the problem, new political choices must be innovated. An aggressive re-planning project must follow up on solutions that recognize, and partially reproduce, the aggregate logic of the first borough. The low-grade urbanism of Silicon Valley cannot remain inflexible; it must instead find a way to compete with the quality of the environment that is now limited to forty-nine square miles.

The Muckraker was played by Albert Pope in Flat Out 3 (Fall 2018).

1 Douglas Rushkoff, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity (New York: Portfolio, 2016), 1. ↩︎

2 In today’s market, doctors can’t afford 58 percent of the homes in the area, according to a study by Trulia. According to a study by Curbed San Francisco, the city’s teachers spend up to 77 percent of their income on housing. Additionally, a Redfin study found that there are no homes in San Francisco County that are affordable for a teacher with an average salary of $59,700. Even the tech companies themselves are not immune. A startup named Zapier is paying employees $10,000 to leave Silicon Valley. Zapier, where all employees work remotely, is offering new recruits a “de-location package” if they’re willing to move away from the Bay Area. ↩︎

3 Aggregation provides for a countless number of outcomes and master planning provides for one; aggregation is highly responsive to fine-grained, block-by-block shifts in supply and demand, while master planning is responsive only to crude shifts in market forces. Master planning does not grow block by city block but subdivision by subdivision. It does not grow office building by office building, but by entire office parks. It does not grow street by street, but by the fixed logic of the freeway. It does not grow store by store, but by the planning of entire shopping centers. Additionally, once a master planned environment is finished, it is finished for good. It lacks the means to grow and evolve over time as aggregate urbanism has always done. ↩︎

4 In their modern incarnation, these temples to capitalism date back to when cities were made up of open-ended aggregations of blocks and streets. The most representative of early twentieth-century corporate headquarters is Rockefeller Center, completed in 1939 in the borough of Manhattan. Today, it is a complex of nineteen commercial buildings covering twenty-two acres between 48th and 51st Streets in the center of Midtown Manhattan. The fourteen original Art Deco buildings span the area between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue and are split by a large sunken square and private street called Rockefeller Plaza. These headquarters have long been considered monuments because they gave a genuine amenity back to the city that made their existence possible. And, like monuments of the past, they were impressive, large-scale constructions, usually made up of simple, platonic forms—spheres, cylinders, cubes, and cones arranged symmetrically. They were surrounded and supported by an open, mixed-use aggregation of blocks and streets. ↩︎

5 Jordan Crucchiola, “SF’s Tech Bus Problem Isn’t About Buses. It’s About Housing,” Wired, February 17, 2016. ↩︎

6 Quoted in Eleanor Gibson, “We Didn't Make Apple Park for Other People,’ says Jonathan Ive,” Dezeen, December 11, 2017. ↩︎

8 The defense of a local, “small is beautiful” ethos has deep roots in the San Francisco region, beginning in the seventies with Sym van Der Rin’s appointment as California State Architect in the first Brown administration. ↩︎

9 Cory Weinberg, “Why Housing Protests in S.F. and Oakland Annoy Urban Planning Chiefs,” San Francisco Business Times, May 7, 2015. ↩︎

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts