Death at

One’s Elbow

The

Mortician

They call it “the law of the instrument”: to a carpenter with a hammer, every problem is a nail. In my line of work it is recently deceased things. Bodies of all shapes, sizes, and ages, lives drained from their mortal form, come through the swing doors at the back of the mortuary. To someone like myself, for whom the whiff of embalming fluid is never far away, it seems (as Morrissey once put it) that “in the midst of life we are in death et cetera.”

My job? Well, to deal with the fact of death. More specifically, it’s to deal with the idea of mortality by processing the physical substance of death. My mortuary is a staging post between the worlds of the living and the dead. On one side, the hospital, accidents, failures, and violence—all those myriad causes of death that haunt life. On the other, the calm chintzy decor of the funeral parlor with its net curtains, marble samples, and brass handles. Between the two lies the mortuary itself. It might look like a lab or an operating theater but what happens in here isn’t science or medicine. Instead, it’s a prep room in which to wrestle with the existential and aesthetic problem of mortality.

Bodies are hard objects to maintain once their life force has left. Gravity seems to act harder on the dead, as if pulling them into the earth. Decay sets in fast. There are leaks and sags in all the wrong places. This slow-motion landscape of decomposition is the canvas for my art, the site where I work to disguise the pallor of death. My work simulates not life but rather an impression of serenity that sits somewhere beyond the traumas of life but in advance of the vermiculated compost that death turns the body into.

Usually it’s a surface job that’s been ordered—a quick once-over to make the deceased palatable to the living at the service. Patching up, filling in, and adding a decorative sheen. Hair and makeup for one last performance before the final curtain. Every so often there’s hard labor involved, a structural alteration, if you like. I might need to reach for my hammer and chisel to crack the spine if rigor mortis has seized the body up into an unnatural crunch. Pro tip: a violent strike can quickly create the impression of deep sleep.

Sometimes it’s a more extensive job, involving not just the surface but the interior too. I do a bit of taxidermy on the side. Just for friends and acquaintances, you understand. If a much-loved pet has popped their clogs or they’ve hooked a prize perch from a weedy pond, it’s me they call on to work some mortuary magic and preserve the emotional sentiment entangled in the physiology of the corpse.

Once they’ve handed off the carcass, I split it open, hollow it, and scoop the fleshy contents out. Into the eviscerated skin I stuff an inanimate armature of wires, sawdust, and old newspaper—un-biological bulk that’s both body and skeleton and neither—that I use to re-sculpt the creature into an imitation of life. In my hands living things become objects, and animals become ornaments with expressions fixed as if by Medusa’s stare. If you need to turn objects into living things, you’ve come to the wrong place. That’s not my calling.

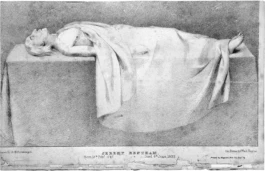

“The Mortal Remains” of Jeremy Bentham, laid out for public dissection. Drawn by H. H. Pickersgill, on stone by Weld Taylor, 1832. Lithograph.

Occasionally, I get a very special commission. I remember Jeremy Bentham, a polymath of the early modern period. In life Bentham was a philosopher, political radical, and legal and social reformer. In death his powers of invention remained just as fertile. Outlined in his will (a little too specifically for a professional like myself) were instructions to mummify and stuff him so as to preserve his bodily form. He called it the Auto-Icon—the transformation of himself into a symbol of himself. Seated and clothed, he is still wheeled through the halls of University College London (UCL) to attend meetings of the College Council. For Bentham, death was not a way to recede from life but to exceed it.

Not to boast, but I did waxy old Lenin too. He still lies in state in Red Square as if waiting to be woken by a kiss, oblivious to the history that has raged around him. My task was to preserve not only the body but also the revolutionary spirit of an entire political and social philosophy. To a humble mortician like myself, it’s quite a responsibility when an entire world order seems to rest on the skills you deploy on the slab. It was just as daunting when they flew me to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to work on the body of Dear Leader Kim Jong-il. This time the job was to preserve a sensation of charisma for eternal life. I worked to merge his physical form with the monumentality and urban planning of the city, so that he and the world he constructed would become indistinguishable.

Even more rarely, other kinds of things come in. Things pronounced dead that require processing in some way: ideas whose electrocardiogram has flatlined; art movements than have stopped moving; pop scenes that have popped their clogs, that kind of thing.

Occasionally, very odd things come swinging though the mortuary doors: inanimate objects that were never really alive, yet now are certainly dead. Things like architecture. Yes—buildings. But also the whole idea of buildings, whole chunks of thinking about how the world could or should or might be.

Let me take you through the process. First of all, it’s important to figure out the approach. What are they after? Is this a funeral, a dignified exit, a monument, or a myth? Or is it a makeover? In which case, it’s just a matter of repointing the brickwork, a lick of paint, a surface overhaul, and hey presto, there’s your building with all the surface marks of death removed, ready to re-emerge in the land of the living!

But sometimes it’s a Lenin-ification they want. That is to say, a transformation from death to myth. What’s demanded here is to turn architectural flesh into an effigy of itself, the architectural equivalent of a Benthamian auto-iconification. You will have seen a few of these, no doubt. Famous houses, for example, from which all sense of life has been removed. They still stand, but like a corpse in a casket—fully present but somehow not at the same time. Polished to a state beyond life, eviscerated of the wear and tear of living into a perpetual perfected monument to itself. Big in California, as you might expect. Neutra in the desert sort of thing.

Others can be unexpectedly difficult. Let’s think. The last big job I had was a thing called Brutalism. There it lay on the slab, the giant carcass of rain-streaked craggy concrete, politics, social welfare, and bold form. Slumped, as sad, gray, and forlorn as an elephant’s graveyard; the tragedy of something that had once dominated the horizon, now collapsed and folded in on itself like a trash bag.

The job was to make this respectable, to make it palatable, and to see architectural death without the horrors of mortality. It was to de-vermiculate, to put beyond the trails of life (not necessarily back to life) so it could once again be inhabited by heroic myths that (between you and me) over-exaggerated their true origin in the first place.

What they wanted was to somehow separate out the tragedy of the life of Brutalism and shift its physical remains into the hallowed space of mythical monument. Physically the stuff was in bad shape. A lot of it partly decayed, its flesh crumbling from its bones. Much of it had already been disposed of, a series of armature demolitions, explosions, and bits hacked off. In other words, it was a mess.

On the plus side, the resource I did have at my disposal was a groundswell of nostalgia from a new generation for an age they could not remember. It was an undeniably rose-tinted view of this moment in history. But more accurately it was a view tinted by Instagram’s complex filters, which highlighted texture and contrast, drained saturation, and otherwise dramatized the death pallor of the subject. Sometimes, that is all you need—a subculture of mythical valorization, a death cult whose zeal can be channeled into a form of eternal life, to make the dead walk among us with new significance.

It turns out that the real secret to Brutalism’s life-after-death was not to treat its physical stuff, nor inject embalming fluid or fluff its surfaces back to an approximation of life. Rather, the secret here was to over-exaggerate its death. Ruin, abandonment, and dereliction could be marshaled not as aspects of death but as an authentic sensation of vitality.

Of course, death and architecture are intimately linked. The first real architect was, in my estimation, Imhotep, who designed the Pyramid of Djoser. This structure was actually a house designed for the Pharaoh, not for his life, but for his life after death. It is like a Russian doll of death, from the embalmed body and the muslin wrapping to the sarcophagus and the stone structure, as layer upon layer of mediation between life and death. This idea echoes through the millennia. And yes, perhaps my job colors my perception. But I would argue that every act of architecture requires its own mortician—architecture isn’t really about creating life, but about fabricating ideas about death. Every building is a renovation waiting to happen, every movement lurching toward a decline that will require resurrection, every architectural idea just something to be first forgotten and then, unexpectedly, recalled. Architecture, it seems, can only really exist after its own death. And that means business is booming.

The Mortician was played by Sam Jacob in Flat Out 1 (Fall 2016).

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts

Flat

Out

Benefactors

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

UIC Office of the Vice

Chancellor for Research

UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts

Flat Out

Flat Out Inc. is a 501 (c) 3 tax-exempt not-for-profit organization registered in the state of Illinois.

Email editor@flatoutmag.org

This website is supported in part by the National Endowment of the Arts